In the shadow of the ongoing covid pandemic, Bernie Sanders has withdrawn from the US primary race, leaving Joe Biden as the presumed Democratic presidential candidate in the upcoming elections. The same week the UK Labour party elected a new leader, Keir Starmer, clearly signaling a departure from Corbynist politics. This marks the end of a recent cycle of left electoralist pushes in these two countries and beyond. Their version of the pink tide is over, but unlike the south american one, it got swallowed by the sea before it even reached the shores.

Less noticed, but perhaps even more telling, was the formation of an initiative called Forward Momentum a few weeks ago. For those that don’t know, Momentum is a group within the UK Labour party formed in 2015 with the aim of pushing the party to the left, and to connect it to the Labour grassroots as well as to social movements. Now, apparently, a faction is needed within this faction, to push Momentum itself towards the grassroots.

Meanwhile it has also been revealed that staffers within the Labour party worked against Corbyn and for a Labour defeat in the election – a story as revealing as it is under-reported in the mainstream media, who have buried Corbyn once and for all, and presumably moved on to greener pastures.

This Monty Python-esque development directly relates to a dynamic that south african labor activist and anarchist Lucien van der Welt described as follows: Electoralism is not a way for social movements to get a foothold in the state, but a way for the state to get a foothold in social movements.

We’ve witnessed the development of ”leftist” parties historically, from the broad trajectory of social democracy as such, to specific instances of socialist or communist parties across the world, and how the closer they are to power, the more they morph into the thing they seemingly set out to change, reform, or defeat. From the aforementioned pink tide in South America, to Syriza, Podemos or Green Parties across Europe, to countless other examples.

There is a common theme here, a dynamic that plays out as these parties march through the institutions of the state.

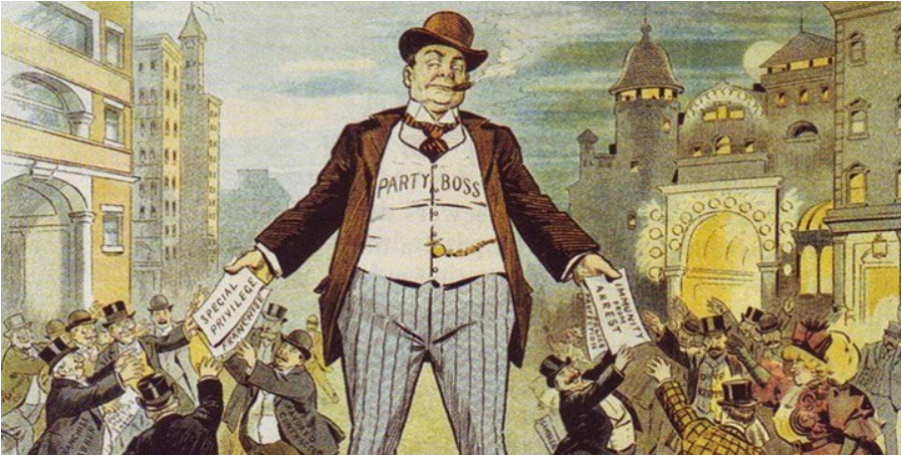

I’ve recently tried to conceptualize these things in terms of a society where all decisions are made by a small amount of people around a very high table. Theoretically, anyone is allowed to join in the decision making, as long as they have stilts so that they can reach up to the table. However, stilts are very hard to come by and require a lot of resources. Now, people come together to try to acquire stilts for “one of their own” so that they can represent the rest at the table. Instead of putting work and resources towards directly trying to improve their conditions by acting for themselves, or putting pressure on the stilted elite – and in the longer run cracking and abolishing the stilts – energy is diverted towards this “pragmatic” project of elevating someone to the table, where, apparently, the real change happens.

A lot of the time this is enough to send meaningful organizing into a quagmire from which it cannot really recover, all without achieving any tangible results, but even if by chance the people succeed and the stilts are acquired, things tend not to pan out the way they were supposed to. This is because at the moment of “ascension”, the chosen representative has to make what I’d like to call the impossible promise: They must promise the others that they will not look down on them, while raising above them on their new stilts. In other words, the issue is not so much about intentionality, as about the structural conditions of the situation that these people put themselves in.

This of course goes far beyond individuals, as Peter Gelderloos put it, in an article discussing localist parliamentary parties in Spain:

Institutions are structurally immune to changes of heart precisely because they operate in complex, mutually reinforcing arrays, because they develop their own subjectivity and identity—their own interests—and the power they deploy can only be used in an authoritarian, centralizing way. Even an entire institution that managed to adopt revolutionary goals would erode the basis of its own power, and eliminate its ability to influence the other institutions, the moment it tried decentralizing power.

This “institutional subjectivity” also stretches beyond the national level, which can be seen in case after case where more or less leftist parties step into state power, like Syriza capitulating to the troika (European Comission, European Central Bank, International Monetary Fund) or the Workers Party of Brazil (PT) accommodating agribusiness as well as international financial institutions and backing down from some of their most ambitious policies even before taking power, in order to become more “electable”. As a telling sample of the resulting political situation, the landless workers’ movement (MST) in Brazil managed to reclaim less land under the PT than under their right-wing predecessor, because their tactic shifted from direct action towards waiting for the PT to solve their problems – something which, in power, they were unwilling to do, because they had to consider the interests of the large land owners and businesses in order to maintain power.

***

In a short Jacobin piece trying to come to terms with the defeat of the Bernie campaign, Paul Heideman acknowledges many of the pitfalls of electoral politics, but then draws a telling conclusion:

It is, of course, true that electoral politics in the United States are institutionally biased against socialists, and that the Democratic Party is run by a corporate-backed establishment that will do everything in their considerable power to stop socialists from succeeding on their ballot line.

But it doesn’t follow from this that electoral politics are uniquely hostile to the Left. After all, if there is anywhere employers have more power than the Democratic Party, it is surely the workplace, and the Left isn’t about to write off struggle in that field.

Yes, class struggle takes place in many spheres of society. However Heideman compares electoral politics with workplace organizing, without noting that the issue at hand is not only where, but also how, and along which lines, we fight back. The workplace equivalent to the electoral strategy of the Sanders campaign is not organizing militant and independent workplace organizations – it is trying to get elected or get someone else elected to the board of directors of the company, or backing a “nicer” person for becoming the next boss, and hoping that these people will enact more benevolent policies from their new position of power.

Just as we should reject such workplace approaches as a surefire way of getting trapped within the existing framework, logic, and power dynamic of the system, we have to struggle in the realm of so called “politics” in a way that doesn’t misdirect and debase our potential power. And this is perhaps they key issue that Heideman misses in his eagerness to as quickly as possible dismiss the threat of anarchism and other libertarian socialist theory and practice in the face of another electoral setback.

Electoral politics are by design an arena in which workers don’t have tangible power, and instead pits them against each other based on superficial ideological divisions. Meanwhile, in our places of work, in our neighborhoods and homes, in the schools, and in all places where our very lives are part of the reproduction of capital, we not only have a material common interest with other working class people, we also have the power to pursue said interest, because in those places we are the ones who make the system run. We are already the ones that make all the stilts.

To return to our “high table” analogy, and as we have already hinted at, the perils of electoralism go far beyond the problems of getting elected. Soon enough, the others at the table will also find ways to sow division between the newly-stilted and the people left on the ground. They will demand that the stilted representative controls the crowd, and tells them to keep calm in exchange for some mild concessions. The people end up fighting for improvements by means which reproduce their oppression and subordination, and those that want to abolish stilts and organize where their real power is at, will be ostracized and painted as purist, irresponsible, and impractical, laying the groundwork for splitting the movement and providing a justification for repressing the part of it that actually threatens the system.

Heideman also contrasts some nebulous concept of “anarchism”, exemplified by running co-ops and dumpster diving, with mass politics. This humorously desperate attempt at discrediting anarchism aside, there is a point to this line of thought if we dig deep enough. Clearly, any political organizing aiming at changing society will have to grapple with tasks of not getting stuck in or breaking out of subcultural or isolated political and ideological bubbles. In fact, almost all uprisings and even revolutions start with a particular spark (increased prices for public transport, food, or gas, austerity measures, etc) and then get generalized as they spread and intensify. But when using the phrase “mass politics” concerning the Bernie Sanders campaign, Heideman only gets it half-right.

Canvassing and voting happens on a mass scale, so much is true. But it is not politics, if by that we mean acting for ourselves to change our lives. Trying to convince people to vote for a particular candidate is not organizing. It doesn’t build any working class capacity to combat and sustain itself against the state and the capitalist class. After the election – no matter who gets elected – the canvassers go home, and we have not necessarily added one single bit of infrastructure to support workplace or community organizing going forward. Even while “winning”, it is possible that this capacity has actually decreased. No wonder russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin called electoralism the “safety- valve” of bourgeois society already 150 years ago.

Mass politics is when we organize to change our conditions where we are at, on a mass scale. In our neighborhoods, as well as in our places of work, and sometimes in the streets. It is not automatically great or successful, but it is crucial in order for us to be able to build actual power outside and against state and capital.

***

But what about the fact that the people of the high table actually make decisions that affect our lives – at times even in a positive way? What about the labor laws, the protections for tenants that exist in some places, anti-discrimination acts, and other positive legislation or meaningful allocation of resources?

Yes, it is true that since they’re monopolizing power, by carrot and by stick, they make decisions that affect us. It is easy to understand how the idea that power and agency originates at the high table can be prevalent in a society where those at said table have control over media, education, infrastructure (and inversely, those in control of these things have their people at the table) and other things that help underpin their position. But it is fundamentally a reversal of cause and effect – it is like thinking that a thermometer causes rather than reflects changes in the temperature.

In similar fashion, electoral politics are largely a reflection of the power relations and stirrings in society at large. They are a reflection of the strength of social movements, and of the balance of power between social classes. The reforms might be signed at the high table, but they are won by class struggle and social movements. Even for relatively worker-sympathetic voices at the high table, positive reform becomes possible to push for while under the uncontrollable threat of well-organized movements of those without stilts.

Or in other words, as another piece critical of electoralism puts it:

Libertarian socialists generally argue that it is the balance of class forces, not the party composition of the political class, that determines legislative and policy outcomes under the capitalist state. If we want reforms in our favor, we must shift that balance through popular organization and mobilization, regardless of who is in power. (Often a wave of new, further left elected officials is a lagging indicator: a resultof that shift, not its cause.)

For those of us that never were big supporters of Corbynism, the Sanders campaign(s) or initiatives like Momentum, it is easy to gloat as they all seem to fall apart or loose their bearings. I however don’t really feel any enjoyment in this particular moment. To me it is disheartening seeing so much energy that could be used to build grassroots organizing which could help us here and now as well as make the stilts obsolete long term, instead spent on rebuilding them and granting them legitimacy, time and time again. The old french slogan from 1968 might go “Be realistic, demand the impossible”, but this is not the kind of “impossible” it meant. It said to be realistic for us, and demand the impossible from them. So can we please stop making impossible promises to ourselves?